The Ábalos case opens PSOE's 'irregular financing': the sewers of Filesa

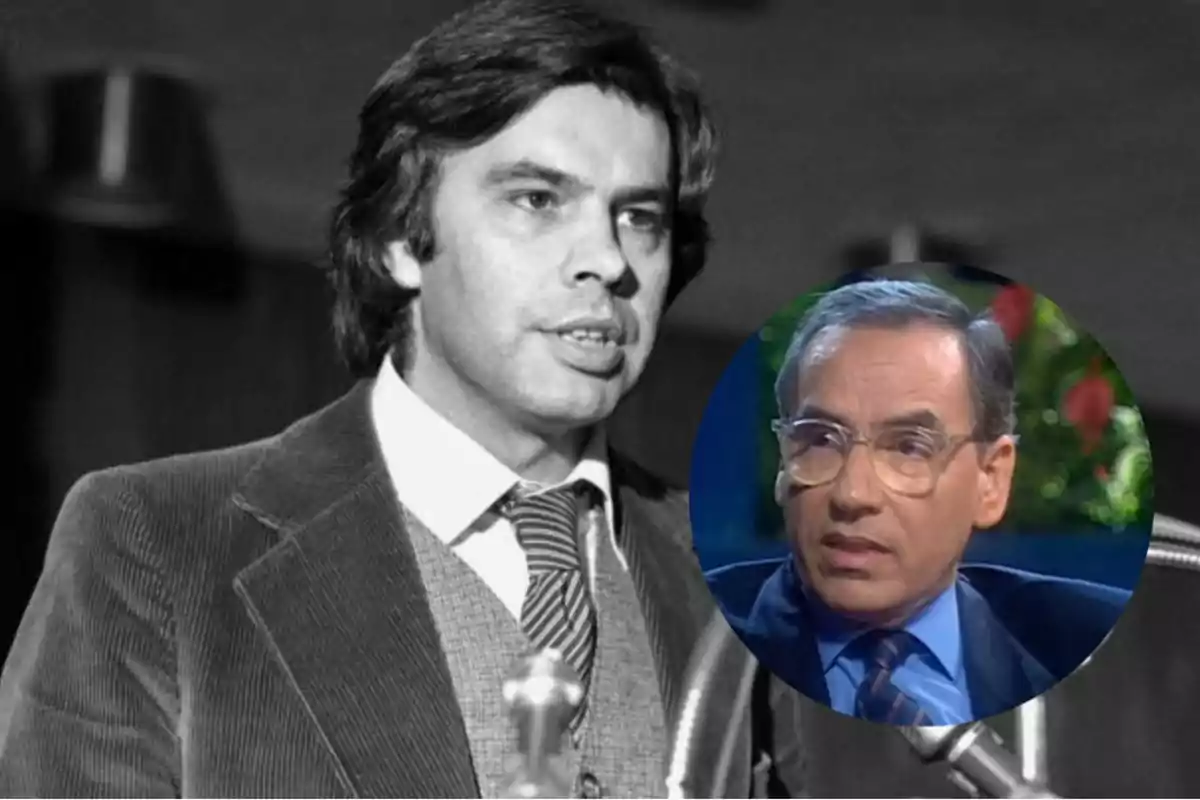

The shadows of the PSOE scandal under Felipe González reappear as the UCO analyzes possible irregular donations

President Pedro Sánchez has replied to the suspicions of irregular financing surrounding PSOE. All this after finding himself "against the ropes" due to the report from the Central Operative Unit (UCO) of the Civil Guard. The report focuses on an alleged network of illegal commissions linked to the so-called "Koldo plot."

The president of the Government has categorically denied the existence of a socialist "slush fund." He attributes the corruption to "isolated cases" such as those of José Luis Ábalos and Santos Cerdán. In addition, he has attributed the accusations to a "misunderstanding" about the party's internal dues, which, according to his defense, are "voluntary and legal."

"The report doesn't contain a single indication of irregular financing of PSOE," Sánchez stated. The president acknowledged that he had considered the possibility of resigning, but he dismissed that option out of institutional responsibility. "Throwing in the towel is never an option," he said.

In a desperate move to regain political initiative and stop the erosion, Sánchez announced an ambitious package of 15 anti-corruption measures, developed with advice from the OECD.

The Government's narrative insists that references to the "tax" within PSOE, recorded in wiretaps, refer to a colloquial expression about the dues that elected officials contribute to the party. This shifts the focus away from an alleged extortion structure, as police reports have suggested.

This new political scandal takes us veteran investigative journalists back to the sewers of power in the 1990s. To PSOE, in this case led by Felipe González.

But what was behind the financing of the ruling party back then, as now with President Pedro Sánchez? Many sewers. Many vested interests, as always, from the top of power. This is their story.

Filesa, the black money schemes in politics

The Filesa case (named after one of the companies in the phantom holding) constitutes one of the most complex scandals of irregular financing of a ruling party (PSOE). The party had received more than 1,000 million pesetas (about 2.2 billion pesetas = $13.2 million) in its coffers through illicit procedures.

In the fall of 1993, the publisher "Temas de Hoy" asked me to write a definitive book about Filesa. Together with my friend and colleague Carlos Berbell.

I knew I was facing a scandal, halfway between corruption and an excessive thirst for power. This ambition had caused a stir and most Spaniards knew of it by reference, but without delving into the heart of the matter.

The judicial investigations caused real earthquakes within the socialist ranks. For the first time, a judge searched their federal headquarters on Ferraz Street as if they were common criminals. Trust between Felipe González and Alfonso Guerra was definitively broken.

The "guerristas" were removed from the central core of the "apparatus" and the president of the Government had to call early general elections in June 1993. All this after the three court-appointed experts assigned to the case delivered a devastating report. The investigations proved the connections between the Filesa holding and PSOE.

From the beginning of the proceedings, the brave and battered judge Marino Barbero was clear about it. He knew that PSOE had set up a network of companies to illegally finance its political campaigns.

The Filesa system

The system was based on disguising the collection of commissions from companies in exchange for concessions, contracts, or favors from the State with fake reports. These reports were granted by high-ranking public officials with maximum obedience.

However, the weak character of the now-deceased judge, who had a renowned academic career, prevented him from taking the vital step out of fear of not finding definitive legal proof. His initial interest faded over time, in parallel with terrible media campaigns orchestrated from La Moncloa that sought to tarnish his spotless image.

But the Filesa holding was only the tip of the iceberg. PSOE was not financed solely at the central level. It had an entire provincial and regional network that operated similarly to this holding. Whose scandals appeared on a smaller scale in local newspapers.

The system was an exact copy of what had happened in France with the company Urba and with the small local socialist networks. An example of this was the one established in the city of Nantes.

To better understand the Filesa case, one must go back in time. See how Pablo Iglesias's spirit was completely broken.

When I spoke with old PSOE members, I found that in the training courses given to them in the local branches, two words always came up to define the socialist essence: ethics and honesty.

Members got the impression they were joining a "pure" and "incorruptible" organization. The only one capable of making "the earth a paradise, homeland of humanity," as the lyrics of the workers' anthem, the Internationale, say.

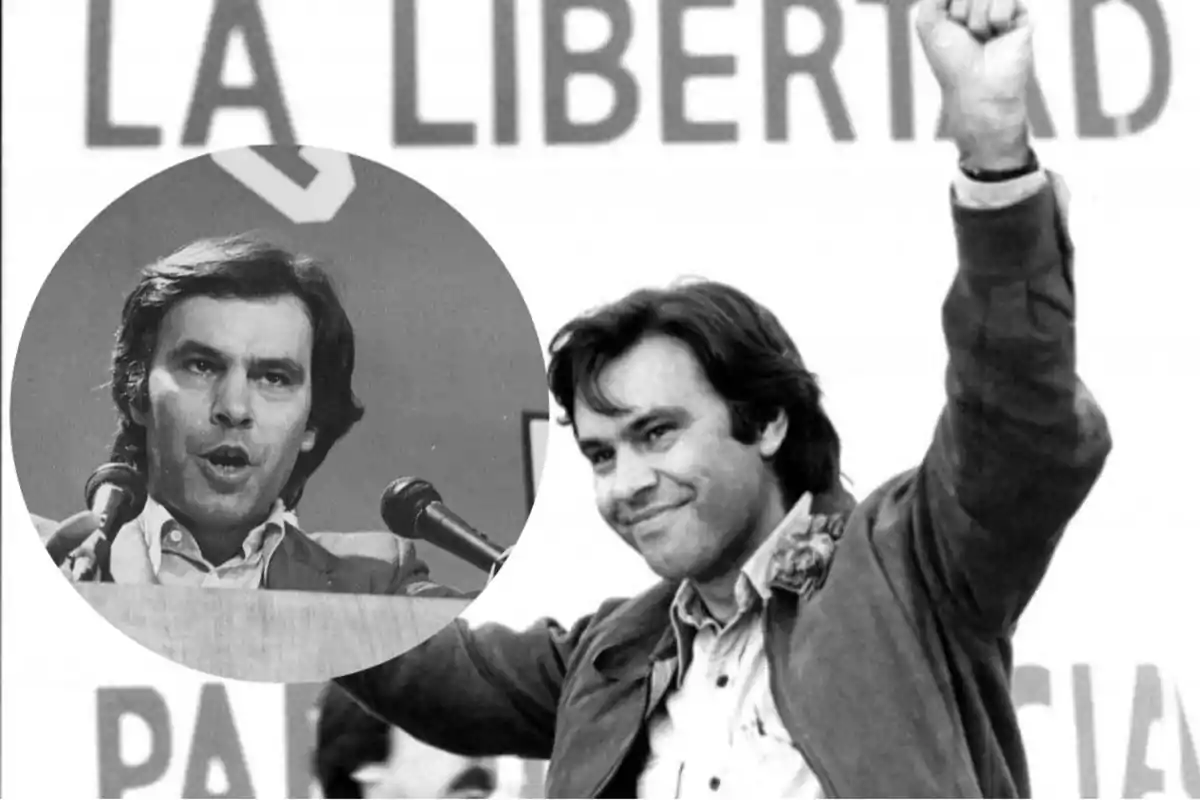

PSOE was the chosen group to put Spain in its place within the international community. Also to ensure that society, after forty years of Francoism, would become more just, supportive, and free. The words of Felipe González and his then number two, Alfonso Guerra, were received as a dogma of faith.

Over the years, socialist membership grew. However, this increase didn't bring with it a rise in assets or finances. The dues never represented a serious source of funding.

When they were collected, they covered only a minimal part of the organizational needs. That's why the top socialist leaders were aware that they needed money if they wanted to participate in upcoming elections with a guarantee of victory.

Every time PSOE participated in general elections, it cost the party more than 1,200 million pesetas (about 2.6 billion pesetas = $15.6 million). The same happened when regional and municipal elections were called.

The solution to the problem of electoral spending

PSOE leaders soon solved this dilemma. In a very easy way: by selling their soul to the Devil. Shortly after the municipal elections of April 3, 1977, in which they achieved their first major victory, they began to finance themselves with commissions from cleaning contracts. Also from construction, rezoning... everything that municipal power could offer.

Later, the system would be applied in the same way from central government and from many of the regional governments. This practice would be kept secret until December 1989, when the first of PSOE's major financial scandals broke out. The Juan Guerra case, one of the party's so-called "fixers" and brother of the then vice president of the Government.

Socialist leaders had already moved from the campaign bus to the private jet. From ham and cheese sandwiches to the delicacies of five-star restaurants.

To alleviate the weak financial health of Spanish political parties, the Political Parties Financing Law was passed in 1987 by parliamentary consensus.

The reason given at the time was the need to address a historical necessity and establish a legal framework to control the finances of the various political parties. Until then, the well-worn briefcase system wasn't criminally punished, since there was no legal regulation on the matter.

With the approval of the new law, PSOE gave up its main system of covert financing. In exchange, it received strong compensation from the State coffers.

Socialist ideologues began to devise a new formula to get easy and quick money. That's why, at the same time this cycle ended, a handful of leaders created the Filesa holding in Barcelona.

The first stone was the consulting firm Time Export S.A., owned by socialist deputy Carlos Navarro Gómez and socialist senator José María Sala Grisó.

This group of companies laundered black money from commissions through invoices issued for non-existent technical reports. A more sophisticated and formal way of carrying out illicit financing.

The fruits of Filesa

Thus, the Filesa scheme became the main source of irregular income for PSOE, parallel to the party's traditional "fixers" route. Among these were Aida Álvarez, Sotero Jiménez, Juan Carlos Mangana Morillo, or Eduardo García Basterra, right-hand man of former PSOE president Ramón Rubial.

The commissions on the total amount of the operation ranged from 1.5% to 3.5%, and even 4.5% in exceptional cases.

The Filesa holding became the vehicle for collecting commissions whose value amounted to more than 1,000 million pesetas (about 2.2 billion pesetas = $13.2 million). Part of which was used to cover the expenses of the various elections held in 1989.

With these "extraordinary" funds, PSOE secretly and by far exceeded the electoral spending limit imposed by the Central Electoral Board. This way, it competed with an advantage over its rivals when reaching citizens with a greater guarantee of success.

However, holding power for more than a decade without interruption made the leaders believe their arrogance would last forever. They were disconnected from reality and abandoned the main hallmark that had always distinguished the party: austerity.

The fall of Filesa

Just as happened with the Juan Guerra case, whose scorned and abandoned wife revealed the scandal, Filesa didn't reach adulthood. This was due to the public denunciation by its accountant, Carlos Alberto van Schouwen.

The Chilean decided to expose the entire nascent socialist scheme after not receiving the 25 million pesetas (about 55 million pesetas = $330,000) his bosses owed him as salary. Out of fear that he would be shot in the back of the head, a threat he had already received.

On April 27, 1992, Van Schouwen was summoned by Marino Barbero. His statement before the judge was altered and distorted, as he himself reported, by the secretary who was processing the records at the time. The Chilean had to sit at the computer and redo it, which shows the pressure he was under.

In the summer of 1992, Van Schouwen would leave Spain disillusioned. A job as a manager in a chemical business awaited him in Santiago, Chile. He returned to his country, alive and traveling light. He hadn't accepted subsequent bribes for his silence.

During his time in Spain, he had dealt a blow to the all-powerful Spanish Socialist Workers' Party. All for a handful of dollars. At the exchange rate, about 25 million pesetas (about 55 million pesetas = $330,000).

In 1996, I met Van Schouwen again in Chile, for an interview I did for El Mundo, five years after this newspaper exposed the Filesa case. The former socialist accountant told me: "That was a bomb, but Spaniards will never know the truth, since they can't investigate the banks. The key is in them and in the black money they move in tax havens."

"Make no mistake, Felipe González knew all about this scheme and benefited from it to win his political campaigns."

The counterpoint of PSOE

If the Juan Guerra case ended Alfonso Guerra's reputation as an honest and ethical socialist, the Filesa case shattered PSOE's image of honesty for many years. It turned "felipismo" into one of the periods of Spanish democracy that was a paradigm of absolute corruption.

However, just as the regime of General Franco did, every time a scandal broke out (Ollero case, Ibercorp, Gal...), the argument of an anti-socialist conspiracy was wielded.

It was always claimed that there was no room for political responsibility, nor for the corresponding resignations, until there was a firm judicial response. Something that in the Filesa case took many years to arrive and was very controlled, in a tangle of political and personal interests that make up the Supreme Court.

Over the years, there's no doubt that the investigation we carried out on Filesa shed light on the underworld of black money in political parties, in the sewers of power and money, both closely linked.

Investigative journalists replied with truthful and credible data to the phrase that the president of the Government Felipe González once used to define this murky affair: "It's an inquisitorial process for a crime we don't know what it is." Today, everyone knows what it is.

The Government of President Pedro Sánchez should know it even more. Of course, the man who was the all-powerful secretary of organization of PSOE, José Luis Ábalos. That is, the hand that rocked Pedro Sánchez to power.

More posts: